Yanis Varoufakis for Unherd: What Trump Wants, and How He Plans to Get It

This is a series of articles by Yanis Varoufakis for UnHerd. Join the DGI live stream with Yanis Varoufakis, Michael Hudson and Ann Pettifor on April 14 12pm NYC / 5pm London time.

***

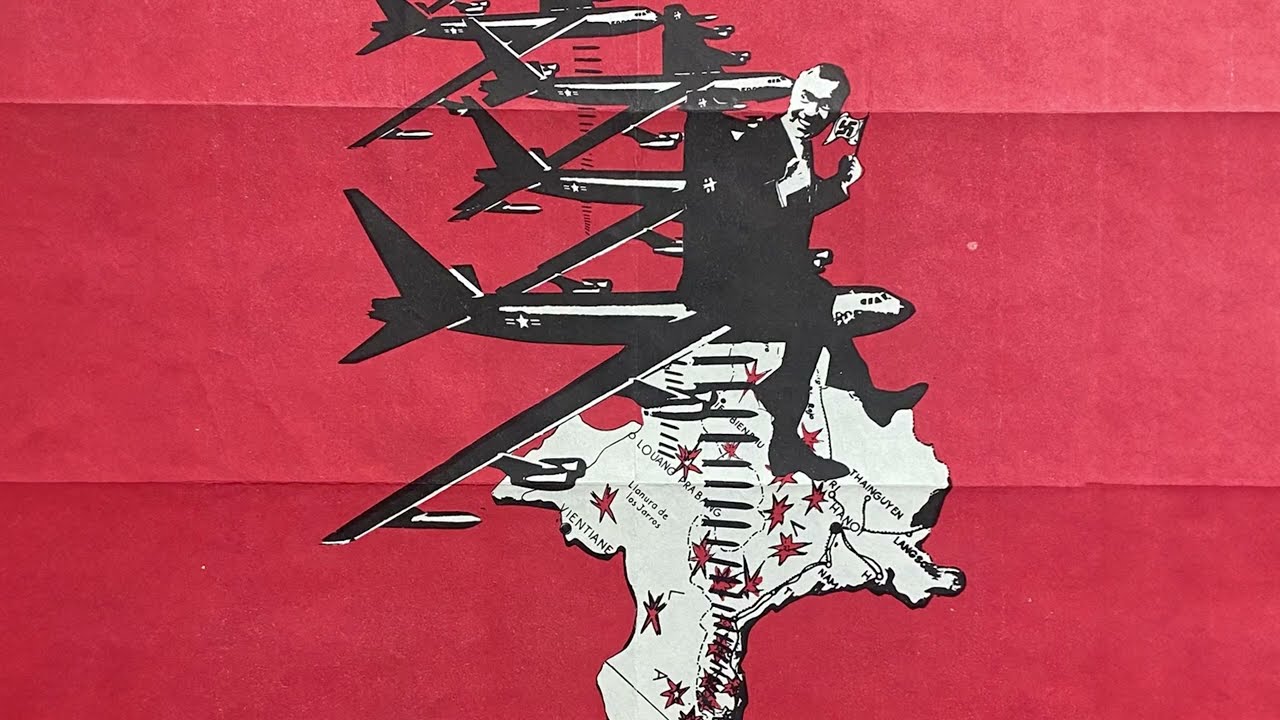

1. Trump’s Economic Masterplan as a new Nixon Shock

Faced with President Trump’s economic moves, his centrist critics oscillate between desperation and a touching faith that his tariff frenzy will fizzle out. They assume that Trump will huff and puff until reality exposes the emptiness of his economic rationale. They have not been paying attention: Trump’s tariff fixation is part of a global economic plan that is solid — albeit inherently risky.

Their thinking is hard-wired onto a misconception of how capital, trade and money move around the globe. Like the brewer who gets drunk on his own ale, centrists ended up believing their own propaganda: that we live in a world of competitive markets where money is neutral and prices adjust to balance the demand and the supply of everything. The unsophisticated Trump is, in fact, far more sophisticated than them in that he understands how raw economic power, not marginal productivity, decides who does what to whom — both domestically and internationally.

Though we risk the abyss staring back when we attempt to gaze into Trump’s mind, we do need a grasp of his thinking on three fundamental questions: why does he believe that America is exploited by the rest of the world? What is his vision for a new international order in which America can be “great” again? How does he plan to bring it about? Only then can we produce a sensible critique of Trump’s economic masterplan.

So why does the President believe America has been dealt a bad deal? His chief complaint is that dollar supremacy may confer huge powers on America’s government and ruling class, but, ultimately, foreigners are using it in ways that guarantee US decline. So what most consider to be America’s exorbitant privilege, he sees as its exorbitant burden.

Trump has been lamenting the decline of US manufacturing for decades: “if you don’t have steel, you don’t have a country.” But why blame this on the dollar’s global role? Because, Trump answers, foreign central banks do not let the dollar adjust downwards to the “right” level — at which US exports recover and imports are restrained. It is not that foreign central bankers are conspiring against America. It is just that the dollar is the only safe international reserve they can get their hands on. It is only natural for European and Asian central banks to hoard the dollars that flow to Europe and Asia when Americans import things. By not swapping their stash of dollars for their own currencies, the European Central Bank, the Bank of Japan, the People’s Bank of China and the Bank of England suppress the demand for (and thus the value of) their currencies. This helps their own exporters boost their sales to America and earn even more dollars. In a never-ending circle, these fresh dollars accumulate in the coffers of the foreign central bankers who, to gain interest safely, use them to buy US government debt.

And there’s the rub. According to Trump, America imports too much because it is a good global citizen which feels obliged to provide foreigners with the reserve dollar assets they need. In short, US manufacturing has been in decline because America is a good Samaritan: its workers and middle class suffer so that the rest of the world can grow at its expense.

But the dollar’s hegemonic status also underpins American exceptionalism, as Trump knows and appreciates. Foreign central banks’ purchases of US Treasuries enable the US government to run deficits and pay for an oversized military that would bankrupt any other country. And by being the linchpin of international payments, the hegemonic dollar enables the President to exercise the modern-day equivalent of gunboat diplomacy: to sanction at will any person or government.

This is not enough, in Trump’s eyes, to offset the suffering of American producers who are undercut by foreigners whose central bankers exploit a service (dollar reserves) America provides them for free to keep the dollar overvalued. For Trump, America is undermining itself for the glory of geopolitical power and the opportunity to accumulate other people’s profits. These imported riches benefit Wall Street and realtors but only at the expense of the people who elected him twice: Americans in the heartlands who produce the “manly” goods such as steel and automobiles that a nation needs to remain viable.

And that’s not the worst of Trump’s concerns. His nightmare is that this hegemony will be fleeting. Back in 1988, while promoting his Art of the Deal on Larry King and Oprah Winfrey, he bemoaned: “We are a debtor nation. Something’s going to happen over the next number of years in this country, because you can’t keep on losing $200 billion a year.” Since then, he has become increasingly convinced that a terrible tipping point is approaching: as America’s output diminishes in relative terms, the global demand for the dollar rises faster than US incomes. The dollar then has to appreciate even faster to keep up with the reserve needs of the rest of the world. This can’t go on forever.

For when US deficits exceed some threshold, foreigners will panic. They will sell their dollar-denominated assets and find some other currency to hoard. Americans will be left amid international chaos with a wrecked manufacturing sector, derelict financial markets and an insolvent government. This nightmare scenario has convinced Trump that he is on a mission to save America: that he has a duty to usher in a new international order. And that’s the gist of his plan: to effect in 2025 a decisive anti-Nixon Shock — a global shock that cancels out the work of his predecessor by terminating the Bretton Woods system in 1971 which spearheaded the era of financialisation.

Central to this new global order would be a cheaper dollar that remains the world’s reserve currency — this would lower US long-term borrowing rates even more. Can Trump have his cake (a hegemonic dollar and low-yielding US Treasuries) and eat it (a depreciated dollar)? He knows that the markets will never deliver this of their own accord. Only foreign central banks can do this for him. But to agree to do this, they need to be shocked into action first. And that’s where his tariffs come in.

This is what his critics do not understand. They mistakenly think that he thinks that his tariffs will reduce America’s trade deficit on their own. He knows they will not. Their utility comes from their capacity to shock foreign central bankers into reducing domestic interest rates. Consequently, the euro, the yen and the renminbi will soften relative to the dollar. This will cancel out the price hikes of goods imported into the US, and leave the prices American consumers pay unaffected. The tariffed countries will be in effect paying for Trump’s tariffs.

But tariffs are only the first phase of his masterplan. With high tariffs as the new default, and with foreign money accumulating in the Treasury, Trump can bide his time as friends and foes in Europe and Asia clamour to talk. That’s when the second phase of Trump’s plan kicks in: the grand negotiation.

Unlike his predecessors, from Carter to Biden, Trump disdains multilateral meetings and crowded negotiations. He is a one-on-one man. His ideal world is a hub and spokes model, like a bicycle wheel, in which none of the individual spokes makes much of a difference to the functioning of the wheel. In this view of the world, Trump feels confident that he can deal with each spoke sequentially. With tariffs on the one hand and the threat of removing America’s security shield (or deploying it against them) on the other, he feels he can get most countries to acquiesce.

Acquiesce to what? To appreciating their currency substantially without liquidating their long-term dollar holding. He will not only expect each spoke to cut domestic interest rates, but will demand different things from different interlocutors. From Asian countries that currently hoard the most dollars, he will demand they sell a portion of their short-term dollar assets in exchange for their own (thus appreciating) currency. From a relatively dollar-poor eurozone riddled with internal divisions that increase his negotiating power, Trump may demand three things: that they agree to swap their long-term bonds for ultra-long-term or possibly even perpetual ones; that they allow German manufacturing to migrate to America; and, naturally, that they buy a lot more US-made weapons.

Can you picture Trump’s smirk at the thought of this second phase of his masterplan? When a foreign government acquiesces to his demands, he will have chalked up another victory. And when some recalcitrant government holds out, the tariffs stay put, yielding his Treasury a steady stream of dollars which he can dispense with any way he deems fit (since Congress controls only tax revenues). Once this second phase of his plan is complete, the world will have been divided into two camps: one camp shielded by American security at the cost of an appreciated currency, the loss of manufacturing plants, and forced purchases of US exports including weapons. The other camp will be strategically closer perhaps to China and Russia, but still connected to the US through reduced trade which still gives the US regular tariff income.

Trump’s vision of a desirable international economic order may be violently different from mine, but that gives none of us a licence to underestimate its solidity and purpose — as most centrists do. Like all well-laid plans, this may, of course, go awry. The depreciation of the dollar may not be sufficient to cancel out the effect of tariffs on prices US consumers pay. Or the sale of dollars may be too great to keep long-term US debt yields low enough. But besides these manageable risks, the masterplan will be tested on two political fronts.

The first political threat to his masterplan is domestic. If the trade deficit begins to shrink as planned, foreign private money will stop flooding Wall Street. Suddenly Trump will have to betray either his own tribe of outraged financiers and realtors or the working class that elected him. Meanwhile, a second front will be opening. Regarding all countries as spokes to his hub, Trump may soon discover that he has manufactured dissent abroad. Beijing may throw caution to the wind and turn the BRICS into a New Bretton Woods system in which the yuan plays the anchoring role that the dollar played in the original Bretton Woods. Perhaps this would be the most astonishing legacy, and comeuppance, of Trump’s otherwise impressive masterplan.

2. Crypto’s role in Trump’s economic masterplan

After dismissing Bitcoin as a scam during his first White House stint, Trump warmed to cryptocurrencies during his re-election campaign. To complete his conversion, on the 6th of March the 47th President signed an executive order to set up a “Strategic Bitcoin Reserve and a US Digital Asset Stockpile”.

The United States government sensibly stockpiles a number of materials that it may need during an emergency, including oil, military gear, medical supplies and, of course, gold. But, if you own the printing presses of the world’s reserve currency, what’s the point of hoarding – on some government owned hard drive – crypto currencies lacking any intrinsic utility? Especially if you have constrained yourself, as Trump has done in the aforementioned executive order, never to sell the crypto you stashed away? The logic of strongarming the Federal Reserve to create a crypto stash, as in the case of every Trump pronouncement, is one part self-serving bluster, one part trolling of his opponents but, also, one part strategy.

The self-serving bluster part was made painfully obvious as Donald and Melania Trump pocketed tens of millions of dollars from the otherwise pointless meme-coins they issued three days before his inauguration. The trolling of his opponents part was also on display as he was signing the executive order forcing the Fed to hold and maintain a cryptocurrency reserve. While ceremoniously putting his exorbitant signature on the order’s dotted line, he beamed with the grin of a cheeky peasant who had just broken into the Baron’s pristine drawing room, spoiling the splendour of its Persian rugs with his muddied boots. That’s how Democrats and mainstream Republicans felt watching Trump elevate the crypto currencies favoured by libertarians, cranks and criminals to the lofty status previously reserved for solid gold and US Treasury bills.

However, in the midst of this cacophony of creepy profiteering, triumph and despair, it is easy to lose sight of the interesting role that Trump’s strategic crypto reserve plays in his broader economic masterplan. And that would be our mistake. Trump’s economic team has a two-pronged strategy by which to recast the global economic order in America’s long-term interests: To devalue the dollar while maintaining its global dominance.

This seemingly contradictory strategy, that would boost US exports (as the dollar becomes cheaper) while pushing down the US government’s borrowing costs (as foreign wealth piles into US long-term debt) is intended to extend US hegemony while also bringing back manufacturing to America. Tariffs, in this context, are the chief weapon by which to pressurise America’s friends and foes to unload their dollar speculative holdings while also buying even more long-dated US Treasury bills.

Be that as it may, what does crypto have to do with any of this? To get a whiff of the answer, take the case of Japanese institutions that hold in excess of $1 trillion of dollars, the result of decades of Japanese net exports to the United States. To drive the dollar down, but avoid strengthening the pretensions to reserve currency status of either the euro or China’s renminbi up, Trump would like to bully Tokyo to dump most of these dollars in the money markets but not convert them into euros or renminbi. What could do the trick? How about convincing, with an element of strongarming, the Japanese to swap their dollars for crypto? That would work, especially if the Federal Reserve dominated the crypto scene. What else could Trump have meant, in the text of his 6th March executive order, when commenting that, while the US already owns considerable crypto assets (the result of confiscations), it “has not maximized its strategic position as a unique store of value in the global financial system”?

More intriguingly, four days later, on the 10th of March, Trump endorsed stablecoins, going out of his way to express his “strong support for the efforts of lawmakers in Congress as they work on bills to provide regulatory certainty for dollar-backed stablecoins and the digital assets market.” In so doing, he added a fascinating new dimension to the idea of forcing non-American institutional investors into moves that serve his economic masterplan.

What are these stablecoins and why does Trump’s economic team look at them as particularly promising tools in the pursuit of their twin strategy? Stablecoins are, by design, a contradiction in terms. The whole point of Bitcoin, the first cryptocurrency, was to stick it to the man – to central bankers and their fiat currencies, the dollar chiefly. But, confusingly, stablecoins are marketed as crypto versions of the dollar. For example, Tether (USDT), USD Coin (USDC) and Binance USD (BUSD) are dollar-denominated crypto currencies that offer you the anonymity, versatility and universality of Bitcoin while also claiming to guarantee full convertibility to the dollar on a one-for-one basis. Indeed, some of the world’s largest banks and non-bank financial institutions are scrambling to launch stablecoins, hoping to capture a slice of a cross-border payments market. Last month, Bank of America signalled it was working on such a stablecoin, following the example of PayPal, Revolute, Stripe and many others.

What makes stablecoins of particular interest to Trump is their promise to keep their value tethered to the dollar. But, how can they promise this and is their promise credible? In theory, this promise can be met if the stablecoin issuer holds, in some vault, one dollar for every token it issued. But, of course, holding zero-interest bearing dollars in a vault would be anathema to any self-respecting financier. So, even if the stablecoin issuer truly owns an equal amount of dollars to the tokens it has issued, it will immediately trade these dollars for some safe, interest-bearing, dollar-denominated asset – like 10-year US Treasury Bills. This way the issuer is true to their word of backstopping their tokens with real bucks while, at the same time, earning interest. It is an arrangement after Donald Trump’s heart and, I believe, at the centre of the idea of his strategic crypto reserve.

By setting up a US crypto reserve containing dollar-backed stablecoins, the US authorities are signalling to dollar-holding foreign dollar holders that the US government is endorsing their ownership of these coins. During the negotiations that Trump plans to have with various governments, with tariffs dangling like a Damocles sword above their head, subtle hints will be dropped that the President will be mightily pleased were foreign investors to buy these stablecoins using their own dollars. If they do buy them, the dollar supply will increase, the dollar exchange rate will dip, no other fiat currency will emerge as a potential suitor to the dollar’s reserve currency status, and dollar-denominated stablecoins will rise in value. As these tokens will now be worth more than a dollar, their issuer will have an incentive to issue more tokens to restore the one-to-one exchange rate with the dollar. In the process, they will buy, with proceeds from the additional tokens they issue and sell, more long-dated US Treasuries to backstop their increased token supply. Bingo! Trump’s twin strategy is served: the dollar will have devalued while demand for long-term US government debt will rise, thus pushing down US Treasury yields and his government’s debt servicing costs.

Upon hearing this, deafening alarm bells should be sounding in our heads. For if this strategy works, and stablecoins become a pillar of the New Hegemony Trump envisages, a timebomb will have been planted in the foundations of the global monetary system. Monetary history is littered with the corpses of outfits guaranteeing the convertibility of some newfangled currency with a time-honoured store of value. The Gold Standard itself was such a scheme, the post-war Bretton Woods system another.

Take Bretton Woods as an example, the Gold Standard’s last evolution and a system whose functioning coincided with capitalism’s Golden Age – the 1950s and 1960s. The idea was that the West’s currencies would be tethered, with fixed exchange rates to the dollar. Moreover, the dollar itself would be anchored to gold at a fixed conversion rate of $35 to an ounce of the magic metal. As long as the US remained a surplus economy, exporting to Europe and Japan goods and services of great dollar value than that of its imports, the system worked fine: America’s surplus dollars were sent to Europe and Japan (in the form of aid, direct investment and loans) and were recycled back to the US with every Boeing jet or Westinghouse refrigerator that European and Japanese customers purchased using the dollars that had come their way.

Alas, by the late 1960s, this recycling system broke down irreparably. The US had turned into a deficit economy, which meant that it began continually to flood Europe and Japan (later China too) with more and more dollars minted to finance US net imports. As long as non-Americans were happy to hoard their dollars, there was no problem. But, the more dollars they had the more sceptical they became that the US government would honour its promise to hand over an ounce of gold to anyone with $35: the makings of a run on gold. Indeed, when several runs on America’s gold took place (the most famous of which involved a French naval vessel arriving in New Jersey laden with greenbacks, to be converted into Fort Knox gold), President Nixon tore up the Bretton Woods agreement, ended the dollar’s convertibility to US government gold and messaged the Europeans, in Trumpian style, “the dollar is our currency but it is your problem”.

So, here is the point: If the mighty US Empire, at the height of its world hegemony, could not honour the fixed conversion rate (of $35-to-one-ounce-of-gold) that was the feted postwar financial system’s anchor, what gives us the confidence to imagine that a private outfit, like Tether or Binance, can do it sustainably? Nothing! Indeed, logic dictates the opposite because of the structure of the incentives Trump is planting with his strategic crypto reserve. Think about it: The more dollars go into stablecoins, the lower the yields on US Treasury bills and the stronger the stablecoin issuers’ incentives to invest in riskier assets – even to issue additional tokens without backing them with additional dollar-denominated safe assets. The more this goes on, the greater the reliance of the US government, and of the global monetary system, on privateers acting responsibly when their incentives are to act less responsibly. Does this classic case of moral hazard remind you of anything? If not, watch The Big Short again!

3. Liberation Day: Will it transform the world?

“My philosophy, Mr President, is that all foreigners are out to screw us and it’s our job to screw them first.” With these words, the US Treasury Secretary convinced the President to deliver a colossal shock to the global economy. In the words of one of the President’s men, the objective was to trigger “a controlled disintegration of the world economy”.

No, those words were not spoken by members of President Trump’s team in advance of their “Liberation Day” tariff splurge. While the “foreigners are out to screw us” certainly has a Trumpian ring, it was uttered in the summer of 1971 by then Treasury Secretary John Connally, who succeeded in convincing his President to unleash the infamous Nixon Shock a couple of days later.

Commentators should know better than to pretend that the shock Trump is now delivering is both “unprecedented” and bound to fail like all reckless assaults on the prevailing order. The Nixon Shock was more devastating than the one delivered today, especially for Europeans. And precisely because of the economic devastation caused, its architects achieved their main long-term objective: to ensure American hegemony grew alongside America’s twin (trade and government budget) deficits.

The success of the Nixon Shock in no way guarantees the success of Trump’s version, but it does remind us that what is good for America’s rulers is not necessarily good for most Americans or, indeed, for the world. One of the smartest Nixon advisers, who helped to convince Connally of the need for a shock, articulated this point with brilliant clarity:

“It is tempting to look at the market as an impartial arbiter. But balancing the requirements of a stable international system against the desirability of retaining freedom of action for national policy, a number of countries, including the US, opted for the latter.”

Then with one additional phrase he undermined all of the assumptions on which Western Europe and Japan had erected their post-war economic miracles: “a controlled disintegration in the world economy is a legitimate objective for the Eighties.”

And 10 months after giving this lecture, the man in question, Paul Volcker, rose to the Presidency of the Federal Reserve. Soon, US interest rates were doubled, then trebled. The controlled disintegration of the world economy, which had started when President Nixon was convinced by Connally and Volcker to dismantle the hitherto stable exchange rates regime, was now being completed with interest rate hikes that were far more devastating than Trump’s tariffs can ever be today.

Trump is therefore not the first President to seek the controlled disintegration of the world economy by means of a devastating blow. Nor is he the first purposely to damage America’s allies to renew and prolong US hegemony. Nor the first who was prepared to hurt Wall Street in the short run in the process of strengthening US capital accumulation in the long term. Nixon had done all that half a century earlier.

And the irony is that the world the Western liberal establishment is grieving over today came into being as a result of the Nixon Shock. While admonishing the idea of a US President delivering a rude shock to the world economy, they are lamenting the passing of what only came into being because of another President’s readiness to deliver an even ruder shock. That is, the Nixon Shock gave birth to the darlings of today’s liberal establishment: neoliberalism, financialisation and globalisation.

The Nixon team’s fundamental question was: how could America remain hegemonic once it became a deficit country? Was there an alternative to belt-tightening which would risk a recession and curtail America’s military might? The only alternative, they surmised, was to do the very opposite of belt-tightening: to boost the US trade deficit and make foreign capitalists pay for it (the “screw them before they screw us” strategy that Connally convinced Nixon to adopt).

Their audacious strategy to make foreigners pay for the US twin deficits relied on creating circuits of capital by which foreign dollars could be repatriated and then recycled. That meant unshackling Wall Street from all the constraints placed upon it under the New Deal, the War Economy and the Bretton Woods system. After four decades of controlling the bankers so they would not inflict another 1929, Nixon’s team liberated them. But doing so required a new economic theory wrapped up in a suitable political ideology.

Under neoliberalism’s ideological and pseudo-scientific cover, bankers found themselves with billions of foreign dollars to play with in a deregulated environment: financialisation. The more this new world system relied on US deficits that generated the necessary demand for European and Asian exports, the greater the volume of trade necessary to stabilise this purposely imbalanced globalised system. And thus globalisation was born.

Many refer to this world — the one in which Gen X grew up — as the neoliberal era, others associate it with globalisation, some identify it with financialisation. It’s all the same thing: the world the Nixon Shock begat and which the 2008 financial crash shook to its foundations. After the 2009 bailouts, although US hegemony continued unabated, it lost much of its dynamism. Today, the Nixon Shock has run out of steam — at least from the perspective of the Trumpists who want to give US hegemony a second (or is it a third?) wind. This is the whole point of the Trump Shock and its masterplan, including tactical moves such as enlisting crypto to their cause.

But there are differences between the two shocks. While both aimed substantially to devalue the dollar while also strengthening its exorbitant privilege to be the world’s reserve currency, the means were different. The Nixon Shock relied on letting money markets devalue the dollar’s exchange rates, adding further pain to America’s allies through the explosion in the price of oil – which damaged Europe and Japan significantly more than US producers. Trump might be taking a (small-ish) leaf out of Nixon’s book regarding oil prices , but he is trying to make his tariffs to for him what the Volcker-led Federal Reserve had used interest rates for: as a weapon that inflicts more pain on European and Asian capitalists than it does on American ones.

The outcome of the Trump Shock will depend on whether it has staying power, for which it will probably need bipartisan support. After all, Nixon’s equivalent worked because President Carter appointed Volcker to the Federal Reserve and allowed him to continue the Nixon project unhindered; before President Reagan turbocharged it further with the help of Alan Greenspan whom he appointed in 1987 to succeed Volcker. Is the US political system still capable of that degree of bipartisanship? It seems unlikely but, then again, who would have imagined that Biden would embrace Trump’s China tariffs and escalate the New Cold War his predecessor started?

And if the Trump Shock has anything like the success of the Nixon Shock, what will this world look like? Perhaps it is too early to tell, but neoliberalism is already being contested by the technofeudal creed of neoreactionaries such as Peter Thiel. Cloud capital is displacing financial capital and replacing the divine role of the market with the holy grail of the transhuman condition (the merger of cloud capital, AI and the biological individual). Financialisation will soon be under similar pressure. As AI develops, Wall Street will not be able to continue resisting the merging of cloud capital and finance, such as Elon Musk’s ambition to turn X into an “everything app”. Such developments will do to payments what the internet did to fax machines, with serious repercussions for financial stability, including any future role for the Federal Reserve. And in place of the dream of a Global Village, we will have the Walled Nation. Nevertheless, that globalisation recedes does not mean that autarky is possible. The Trump Shock is, thus, pushing us into a Bisected Planet, one part of it comprising vassal countries that have yielded to the Trump Plan and a second part where the BRICS experiment is allowed to take its course.

Every generation likes to think it is on a cusp of some historic transformation. But ours is cursed enough to actually be on such a cusp. So rather than focusing too much on the character of the man in the White House, we would do well to recall that the Nixon Shock was much more important than Nixon. If Nixon reshaped the world once, leaving it nastier and more unbalanced, Trump can certainly do it again.