Interview with Adrian Bowyer

3D printer that prints itself

Translation of Nika Dubrovsky’s 2011 interview with Adrian Bowyer

The best Christmas present for yourself is a 3D printer. You can buy a reasonably priced model in the UK for less than £900. This printer differs from the well-known two-dimensional printer in that it prints objects. A true embodiment of the traditional wish “whatever you wish for yourself.” Now you can print. For now – out of plastic.

A three-dimensional printer works with three-dimensional information. Technologically, a 3D printer is quite simple: the printer, connected to a computer, prints the desired object layer by layer, using some fusible plastic.

A new stage in the development of technology––three-dimensional printers capable of printing themselves. Three-dimensional printers appeared quite a long time ago, but due to their high cost, slowness, and limited range of materials that could be used for printing, they still exist as marginal techno-toys.

In recent years, however, 3D printing technology has shown rapid growth. Not only scientific developments, but also active projects have appeared.

In St. Petersburg, the Midgart center for volume printing helps designers print layouts (this technology, in particular, is very useful for designers of jewelry), gamers can get high quality and inexpensive printed from plastic personal avatar.

Many companies provide their customers with art shop services: from printing the sculpture they like (just send us a file!) to making portraits of tombstones.

There are also individual artists who print out their own computer-modeled sculptures on a home 3D printer and mail them out to customers. Technology advances––technology becomes cheaper. In 1985, when the first personal printer (for flatbed printing, of course) Apple LaserWriter appeared, it weighed 35 kilograms and cost $6,995. Twenty-five years later, the Desktop Factory 3D printer costs $4995 and weighs 40 kg. While the prices of commercial printers continue to fall, an inexpensive replicating (that is, capable of recreating at least part of itself) three-dimensional printer project is actively being developed.

In order to assemble your own RepRap at home, you just need to buy the materials available in almost any European or American store.

Today, the assembly kit costs about $500, but the creators plan to bring the cost up to $300 in the near future. Consumable materials are also relatively inexpensive––from 7 to 20 euros per kilogram of polylactide, polystyrene, or high-pressure polyethylene.

From them––either by using ready-made 3D models, or by drawing a model of the object yourself––you can print anything the capabilities of such a printer will allow: a coat hook, a salt shaker, three glasses so necessary in the household, etc. but you also can print a necessary plastic details for the 3d printer itself.

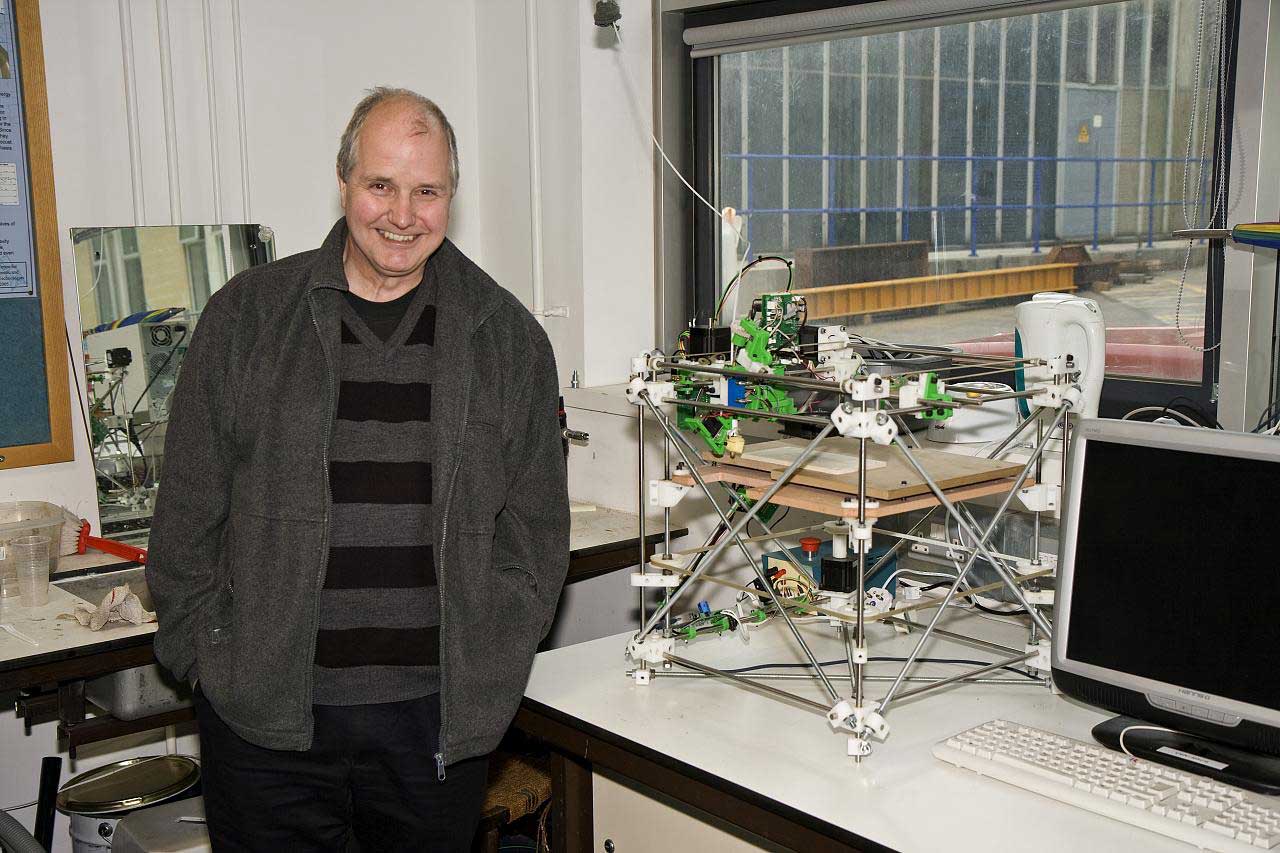

I spoke with Adrian Bowyer, a professor at the University of Bath in the United Kingdom, about the development of the RepRap project.

– How does RepRap differ from other projects that develop 3D printing technology, particularly commercial ones?

– The most important feature of RepRap is that it was conceived from the beginning as a replicating system: a printer that prints itself. Commercial systems would not dare to do it.

It would be suicidal for any industry to create a machine that could recreate itself. Such a machine could be sold only once.

As RepRap contributor Vic Oliver likes to say, “We are not bound hand and foot by the need to make a profit.”

In addition, RepRap is a project with free GPL-licensed code. Absolutely any information needed to build RepRap is available online for free.

– Tell us about the materials that are used for printing.

– The main material we use is polylactide. This material can be obtained from biological materials, in particular, starch.

It is a biodegradable polymer. Eventually, anyone who is able to grow a starch-containing plant will be able to use a 3D printer. In this way, users will be independent of the refining industry that supplies the plastic.

Now we are working on the technology of printing with electrical conductors, rubber, low melting point metals, and ceramics.

– How fast is the research progressing? How many people are involved in the work?

– The main group of developers is ten people. We assume that there are 2500 RepRap printers or their modifications in the world at the moment. The community exchanges ideas and new developments through forums, blogs, and our website.

– Is the number of project participants growing?

– Yes, but I don’t have exact numbers. It’s an open project. The main development team is formed and will not expand, but we always welcome people who build their RepRap and are willing to share ideas.

– Your project seems to be a killer of the commercial printer industry. Is there any danger that you could be shut down or have your work interfered with?

This is not possible. All information is immediately posted online and distributed. Everyone can get it. Thousands of people have already downloaded the specs and built their cars. It’s impossible to take them away, right? What can a commercial company do that gets in the way of our project?

– I really like the science fiction series Star Trek. It combines Soviet science fiction novels and a folkloric version of communism. The society described in the series focuses on science and culture. Production and consumption organised around the slogan: “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs” (German: Jeder nach seinen Fähigkeiten, jedem nach seinen Bedürfnissen) Your article, “Wealth Without Money,” describing a version of a possible future, begins with a quote from Marx and Engels. Why?

– It seems to me that the problem with Marx and the way communism is realized is not that the proletariat must own the means of production, but that in the past it required revolution and a police state to hold onto the gains in order to carry out, to own the means of production.

Many people die in revolutions. And usually even worse societies are born than the ones they replaced (no matter how terrible their predecessors were).

Such a society goes to great lengths to restore what was destroyed during the revolution and to maintain the status quo: few people like living in a police state. State violence costs many lives and suffering. Now look at the recording industry revolution. It was enough to give people high-tech and cheap means of production and distribution, and they began to produce and distribute their own music.

The middlemen and moneylenders were thrown out of the system not because they were shot as class enemies, but because they proved superfluous.

I want all manufactured goods to be in the same situation as music distributed over the Internet today, and all commodity production to repeat the fate of the record industry.

– Over the past 20–30 years we have seen the realization of the most incredible science fiction fictions. The communicators from the TV series Star Trek defined the appearance of the first cell phones. Do you think we will see food synthesizers in our lifetime?

– Many people already use RepRap today to create cakes or chocolate. True, you need the right ingredients for that. However, the source materials for the rest of the objects that RepRap prints are also supplied from the outside.

In both cases, it is best to use materials derived from plants. They grow on their own, requiring almost no care, and everyone can use them for free.

Adrian’s optimism, however, is not quite correct – he is talking about plants already ready for consumption, while crops require at least some amount of land.

Independant Journalist, published the interview, accompanying it with editorial comments:

P.S. From the Editor: In its current form, the RepRap website has already posted documentation for the second version of the system, named after the father of genetics, Mendel, which, to put it mildly, is not fantastically perfect.

There is little precision in printing, even simple things turn out rather sloppy. The stroke of the head is too great, and therefore the glasses cannot boast finesse.

But, in essence, these are all natural costs of the formative period of technology. If anything RepRap reminds us most of, it was the first mechanical printers with needles and ribbons of ink.

Over several decades, mechanical printing technology has moved into a fairly narrow niche of commercial equipment, with the more advanced laser and inkjet printing becoming mainstream.

Apparently, the same will happen with 3D printers: both commercial samples, protected by patents and using proprietary software, and uncomplicated devices such as RepRap, produced on the basis of open source, will become cheaper.

And the competition between them will take place, apparently, according to the same rules that have been going on for many years between commercial and open source software, that is, slowly, in leaps and bounds, provided by large corporations like Sun, IBM, and Google that support open source software in the struggle against proprietary software producers.

However, this is not the only thing that makes the entry of open source principles into the real, physical world remarkable: RepRap is a kind of tool for the cognitariat, the information artisans, the intellectual proletariat of the post-industrial society, which, in fact, can only with RepRap find its way beyond the limits of corporate industrial production.